On December 17, Novonor held its Annual Meeting, an event that brings together leaders from the Group’s companies to...

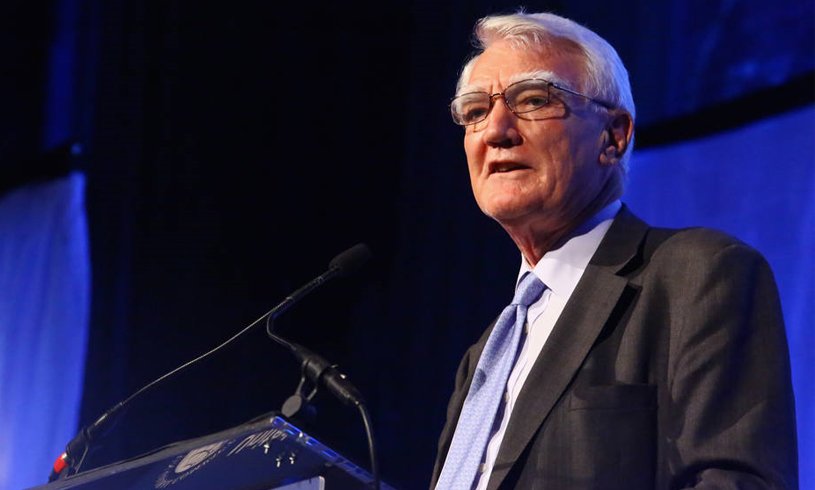

Read the interview given by Mark Moody-Stuart

DATE: 11/01/2017

Read the full interview given by Mark Moody-Stuart to the Brazilian newspaper O Estado de São Paulo. According to the councilmember, the group can be fixed, but must follow all steps of the process

O Estado de S.Paulo. November 1, 2017

Executive Mark Moody-Stuart talks about tough topics in the corporate world with the serenity of someone who’s seen it all over his 77 years. At the helm of Shell from 1998 to 2001, he led the oil giant when it was striving to overcome a severe reputational crisis, following accusations of environmental damage and involvement in human rights violations in some of its operations. Now, he wants to save Odebrecht, a company that confessed to creating one of the largest bribery schemes ever seen anywhere in the world.

He is a member of the Global Advisory Council, a group recently created by the Brazilian conglomerate that is charged with the mission of supporting its restructuring process. Moody-Stuart, who also served as chairman of the mining company Anglo American and currently sits on the board of oil producer Saudi Aramco, said Odebrecht can be fixed, but that it will take time. “It’s a bit like the Alcoholics Anonymous, with their ten-step program,” he said in his interview to Estado.

According to him, this is a great time to be in business with Odebrecht, since its activities are being supervised by various monitors. “If you want clean business activities, Odebrecht is an excellent alternative. Any misstep they take could really blow up everything and probably lead to the organization’s demise. They know it’s a matter of survival and they have to get it right.”

We continue to see major cases of corruption involving multinationals. Are they refusing to change?

That’s an interesting question: do they refuse to change or have they changed in the wrong direction? (laughs). The fact is that this is certainly not a new phenomenon. Anyone who believes in markets works against corruption. You can talk about ethical reasons, but there’s the motivation that this causes a distortion of the market. Now, if a company doesn’t want to pay bribes, preventing that is relatively easy. Just say “we won’t pay bribes,” establish principles and rules and don’t pay them. To many large companies, the big challenge is what I call “the outside bribe.”

What is that?

There is a big project (that the company wants to compete for) and the company must be alert to whether its competitors are working together to conspire or trying to bribe some of its employees. It also must be alert to whether any of its employees are asking for bribes.

Companies usually worry about that when they already have a problem.

The biggest challenge is to make people understand that have to worry about it beforehand. Leading companies are often those who have weathered crises. When a responsible company has a crisis, the self-esteem of everyone at the company is affected. Shell went through that in 1995, in the wake of two major crises. One a human rights crisis with the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa (Shell was accused of conniving with the Nigerian government, which executed activists, including writer Saro-Wiwa), and the other was an environmental crisis, with the plan to dispose of an oilrig under the North Sea. We had principles, including anti-corruption, and we thought we were responsible citizens. Before 1995, if you entered a bar and said you worked with Shell, you were respected. After that, less so. So, you have to fix it, because it affects everyone at the company.

Considering Odebrecht, is it time, then, to think more about the morale of employees than the opinion of those outside the company?

Probably both. Odebrecht was a reputable, highly regarded company. The crisis came and brought with it the same situation as Shell in 1995: “You work for Odebrecht? Oh, the bribery scandal.” There’s a problem of self-esteem. And entire businesses of Odebrecht were not the targets of accusations (of corruption). Looking back, what was done was: step one, Emílio Odebrecht said “we’re guilty.” Step two: publishing the ten principles, which are very powerful. Then you need examples: that you didn’t do something, that you were not awarded a contract and that it cost you money in the short term because of these principles. And then everyone at the organization will be comfortable in saying: we don’t do that (paying bribe). That is very powerful. The goal has to be to establish internal trust. Then the external trust will come.

But does that work when the principles are coming from people wo used to lead the business before?

The people who were directly involved are no longer with the company.

Emílio Odebrecht is…

Yes. You face it as a challenge. When Georg Kell (German executive who created the UN Global Compact) and Sérgio Foguel (member of Odebrecht’s Board of Directors) asked me to join this Board, I researched what Odebrecht was doing. I saw this public statement (of Emílio Odebrecht), I looked at the principles and I thought to myself: it looks good, the question now is how are you doing it. Odebrecht is important to the Brazilian economy, it’s almost a Brazilian icon, a company I knew from before my days at Shell and Anglo American. If you asked about Odebrecht, I’d say “of course I know it.” I’m sure we probably had contracts with it – and I’m equally sure they were not corrupt contracts… But, who knows? (laughs). So, when this company, which employs tens of thousands of people, asks if we want to help it solve this problem, the answer is ‘yes’. If you’re really committed to solving the problem, then the answer is yes, because it’s an important job to help fix such an important economic player. Some (businesses) may be beyond repair.

Can Odebrecht be fixed?

Yes, absolutely. Maybe I shouldn’t say this, but it’s like the Alcoholics Anonymous, which has a ten-step program. The first step is going into the meeting and admitting: “I’m an alcoholic.” Then, there are rules. Then you have to make sure you will encourage people to really believe those rules. In the case of Odebrecht, they put in place compliance committees reporting to the board. But, more importantly, there are monitors from the U.S. Department of Justice and from the Brazilian authorities. There are dozens of monitors sitting throughout the company. In a way, I can say I know for a fact that these guys aren’t doing anything wrong now, because they have monitors watching them from all sides. If you want to do good, clean and correct business, Odebrecht is now the best company for the task. Look at the controls they have in place. Not only internal, but external. You know it’s all OK.

Does the transformation of image necessarily take time?

It depends. Does regaining the trust of external stakeholders take time? Yes, because people can say: “Odebrecht? Oh, I remember, the one with the crimes, the wrongdoings.” And that’s understandable. Now they’ve put systems in place and have an opportunity to become a role model. Odebrecht can’t just say, this is the company we used to be – a construction, engineering, petrochemical company – only it’s clean now. You have to address society: “What are our obligations?” This process will take a lot of time. People have to think about it. These are not just anti-corruption principles. You had a car accident, it was your fault, because you were drinking and driving or something of the sorts, and you think: ‘I almost died and have to learn not only how to drive properly, but to rethink the rest of my life. Why am I here?’ That’s the process. Employees are quite depressed, because of the recession and everything that’s happened. They have to start feeling that they can solve the problem, that they don’t have to feel embarrassed about working at Odebrecht.

How can you conciliate the need to keep away those involved with the fact that they have important knowledge for the organization?

Generally speaking, the people who were involved are no longer with the company and they cannot go back. At one of the companies I’m a part of, Saudi Aramco (the state-owned Saudi Arabian oil company), which is another interesting family-owned company, with the difference that the family also controls the country…

Well, at some point, you could say Odebrecht ran the country here too.

(laughs) The company has to look at where it’s going. So far, I’m satisfied and we’ll have to see how Odebrecht does the other things. They have the mechanisms to mobilize and motivate. They’re not starting from scratch. They have a company with strong systems. They only have to make sure that this system is delivering properly.

The fact that this is a family-owned company, does that make things more difficult? What should be the family’s role going forward?

The Odebrecht family owns the company. That won’t change – well, it could change, I don’t know. For a normal corporation, the shareholder is not involved in running the company. The same goes for Saudi Aramco: it elects the Board, approves the audits, receives the accounting statements. It doesn’t put its finger on the management. At Odebrecht, the family will remain at the holding company. They are taking care of that.

Would it make sense for Odebrecht to change its name?

If it simply changes its name now, everybody is going to say: “Come on, you’re just calling an elephant a rhino and expecting me to believe you’ve become a rhino.” But, if the elephant turns into a gazelle or into a racing elephant, you can call it Jim instead of calling it Jambo, or something to that effect (laughs). My immediate instinct would not be to say to change their name. The name isn’t the problem. The problem is their reputation. If they fix the reputation, then they could say they entered into a joint venture with another company and maybe adopt a new name. Otherwise, it would be a waste of time. The name, in spite of everything, is still valuable.

Why?

If someone told me one of my competitors was a construction company called Odebrecht, I’d say: “I’ve heard of them, they’ve built major projects efficiently, won awards, I know who they are.” My second question would be: “Are they clean or will I damage my reputation by doing business with them?” I’d say that, with the steps they’ve taken, now they wouldn’t damage my image.

Will it be easier for Odebrecht to change its image abroad?

It’s basically the same challenge or even more difficult. In Brazil, most people know the problem isn’t Odebrecht. It’s a bigger problem. Look at Petrobrás, the government, the allegations of corruption… Outside Brazil, you can try to escape the issue by blaming only that foreign company called Odebrecht. I’d tell these governments or anyone in the world that, if you want to do business completely legitimately, Odebrecht is a great alternative. Any misstep they take could really blow up everything and probably lead to the organization’s demise. They know it’s a matter of survival and they have to get it right. Any company would like to leave this problem behind sooner rather than later, nobody likes to work under that level of supervision. But it’s part of the cure: continuing to take your pills.

No comments